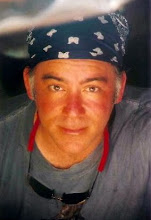

Saturday, Lily and I went to her favorite restaurant for lunch. Thankfully she is now eating off the menu which makes our outings easier as I no longer have to pack a meal for her. She loves the diner. It is loud, bustling, has seats that attach to the table and if she's lucky, she'll be seated in a booth with a mirrored backdrop so she can show herself french fries in the reflection and leave her fingerprints behind. She eats with gusto, and is well practiced at loading up a mouthful as though food were going out of style. She devoured grilled cheese bits, fries, had some pancake and sausage - all while occasionally turning around to point to the men in the booth behind us. Lily now identifies everything as "dah" and typically she is quick to find all children in the restaurant. She then fixates on them, offering an occasional shriek or squeal to get their attention - and is thoroughly entertained as she eyes them while dabbling with containers of creamer and metal spoons. But Saturday it was all about the two men facing her when she turned around. And for a moment my heart sank. As she pointed to them she said "dah" and with that my mind began spinning. Immediately I wondered of she thought one of them was her dad. They really bore no resemblance to Alan but she sees pictures of him all the time and on a superficial level, they did share characteristics. They had scruffy faces and dark hair. Possibly enough for an eleven month old to believe. It was my first taste of "is she looking for him?" and I must brace myself for more similar experiences to come. I dread the ache she will feel when she sees other kids walking to school, swinging from the hands of parents on either side. I dread the absence she'll feel when being picked up at the end of the day. Many children face similar situations with just one parent but I am envious that some of them know that they'll see their father at dinner or perhaps he'll tuck them in that night. And if not that night, sometime soon they'll see them.

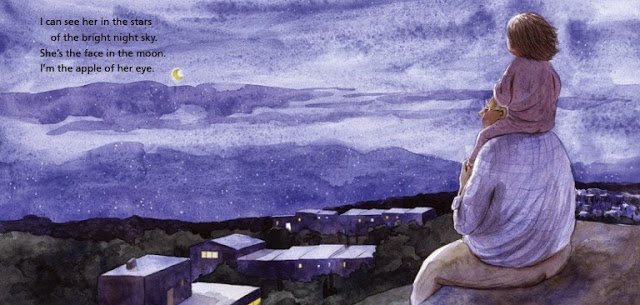

Some have told me that what children never know, they don't miss. That idea is both a comfort and nightmare. I want Lily to know who her dad is, was, I want her to know his many wonderful qualities. I want her to be able to imagine the softness of his voice, the strength of his arms, the warmth in his heart. I want her to feel as though his arms are always around her, and that whispers in the wind are his words of encouragement, that he's always there right by her side - In her steps as she walks with me to school, and in my excitement as I lift her into my embrace when I pick her up at day's end. I don't want her searching for him, I want her to know that she's found him within her. My greatest wish is that she feel complete - loved by us both, always.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Sunday, January 24, 2010

More to fear, much to learn.

There is a horrifying article on the front page of the NY Time's today: "A Lifesaving Tool Turned Deadly". I had been warned not to read it but, of course, I felt compelled to do so. Despite the fact that the fight we were engaged in is over, I still feel compelled to follow medical updates that pertain to Alan's life, and my life. The fantasy is that it has nothing to do with the treatment that Alan endured, the horror rests in the fear that it does. And then more troubling, I will probably never know. The story tragically illuminates multiple, undisclosed until now, cases in which cancer patients were given fatally errant doses of radiation treatment. Computer glitches accompanied by incompetent staff have robbed many people of their lives - in essence, technology failed and then human negligence sealed the deal. What is most frightening is that never ever in our consideration of Alan's treatment did we concern ourselves with such a threat. We were aware of the risks of radiation and knew it came with its own problems but the illness outweighed the long term risks associated with the treatment. We consulted with doctors in San Francisco, Boston and New York city. We insisted on the "best" institutions and sought out the most highly recommended experts to handle Alan's case. But never did it cross our mind to inquire about software failure, computer crashes or inattentive staff.

When you're immersed in the world of cancer you are well aware of the physics that go into plotting your treatments. Numerous 360 degree scans are taken to zero in on the disease, tattoos are used as permanent markers by lab technicians as targets, a week can be spent plotting and programming radiation doses and beams, molds are taken to further ensure the patient is held completely still during sessions, sedatives are often used to keep patients relaxed and still for what are often excruciatingly long and claustrophobic appointments. I was always in awe of Alan's strength, inner calm and courage - he was subjected over the years to months of treatments. Some sessions lasted ten minutes, some an hour. It required infinite patience and he was heroic. I remember appointments when I'd be in the waiting room and after twenty minutes sometimes a tech would come out and kindly give me or other people updates on their loved ones. Sometimes it was "he's doing fine but we're having trouble lining him up with the machine", sometimes it was "she's having a rough time and we're having difficulty maintaining enough stillness to finish plotting - we'd like to let her go home for the day and try again tomorrow". Sometimes it was "we're getting him an atavan because it's taking us longer than usual". I remember one of the last sessions Alan had, our favorite nurse practitioner, Joan, came out and said "He's having a rough time in there today, he's doing OK now, but do you want to go back there for a bit?" I jumped at the opportunity. To hear that Alan was struggling was unusual but he had been through so many unimaginable trials over the months preceding that it was finally catching up with him emotionally. To hear that he was having a hard time was heart breaking and I was led back to where the techs were. I must say, after reading the article I was fearful of error in Alan's case, but what I saw that day was reassuring. Two techs had their eyes glued to computer monitors and occasionally one would focus on Alan on the camera screen overhead. When patients are undergoing treatment techs talk to them over speakers so they're never meant to feel alone or unattended. I was able to talk to Alan but I don't think I actually did that day. I asked that they tell him I was there just so he knew. I didn't want to make the situation more loaded, I just wanted him to know I was there, watching him and waiting for him.

But with all of the skepticism we have for our doctors and hospitals I don't think many imagine that "state of the art technology" can go awry. And we assume that if good doctors are overseeing the treatment, that there is little room for error. I continue to believe that that was the case for Alan. Yet Alan did not die from cancer. He died from complications from treatment. Generally unexplained complications from treatment. Doctors suspected the complications were inevitable side effects from prolonged treatment and as the disease spread his situation became more and more dire - but I hope, I pray that his overall treatment didn't hasten his passing. The stories mentioned in today's article were horrendous examples and showcased patients that had been blatantly mistreated - I do not think Alan was a victim of similar circumstance. He was a victim of an incurable disease and dangerous treatment that never promised anything. If Alan were here today reading that article he still wouldn't be angry at the injustice of it all. It wasn't in his nature. He'd perhaps want to discuss it with his doctors but then he'd leave it at that. I on the other hand would be ready to call our doctors to reaffirm he was and had been in good hands, I'd have written letters and contacted the president of the hospital just to double check. "Soapbox Susie" is what Alan called me when I ranted about similarly infuriating exposees. Tonight he'd surely call me that. But after reading this article, one can't help but wonder about any radiation treatment that anyone has ever received and it certainly is worth asking about if ever faced again.

Deep breath. Sigh. Must go check on Lily, just to be sure of her.

When you're immersed in the world of cancer you are well aware of the physics that go into plotting your treatments. Numerous 360 degree scans are taken to zero in on the disease, tattoos are used as permanent markers by lab technicians as targets, a week can be spent plotting and programming radiation doses and beams, molds are taken to further ensure the patient is held completely still during sessions, sedatives are often used to keep patients relaxed and still for what are often excruciatingly long and claustrophobic appointments. I was always in awe of Alan's strength, inner calm and courage - he was subjected over the years to months of treatments. Some sessions lasted ten minutes, some an hour. It required infinite patience and he was heroic. I remember appointments when I'd be in the waiting room and after twenty minutes sometimes a tech would come out and kindly give me or other people updates on their loved ones. Sometimes it was "he's doing fine but we're having trouble lining him up with the machine", sometimes it was "she's having a rough time and we're having difficulty maintaining enough stillness to finish plotting - we'd like to let her go home for the day and try again tomorrow". Sometimes it was "we're getting him an atavan because it's taking us longer than usual". I remember one of the last sessions Alan had, our favorite nurse practitioner, Joan, came out and said "He's having a rough time in there today, he's doing OK now, but do you want to go back there for a bit?" I jumped at the opportunity. To hear that Alan was struggling was unusual but he had been through so many unimaginable trials over the months preceding that it was finally catching up with him emotionally. To hear that he was having a hard time was heart breaking and I was led back to where the techs were. I must say, after reading the article I was fearful of error in Alan's case, but what I saw that day was reassuring. Two techs had their eyes glued to computer monitors and occasionally one would focus on Alan on the camera screen overhead. When patients are undergoing treatment techs talk to them over speakers so they're never meant to feel alone or unattended. I was able to talk to Alan but I don't think I actually did that day. I asked that they tell him I was there just so he knew. I didn't want to make the situation more loaded, I just wanted him to know I was there, watching him and waiting for him.

But with all of the skepticism we have for our doctors and hospitals I don't think many imagine that "state of the art technology" can go awry. And we assume that if good doctors are overseeing the treatment, that there is little room for error. I continue to believe that that was the case for Alan. Yet Alan did not die from cancer. He died from complications from treatment. Generally unexplained complications from treatment. Doctors suspected the complications were inevitable side effects from prolonged treatment and as the disease spread his situation became more and more dire - but I hope, I pray that his overall treatment didn't hasten his passing. The stories mentioned in today's article were horrendous examples and showcased patients that had been blatantly mistreated - I do not think Alan was a victim of similar circumstance. He was a victim of an incurable disease and dangerous treatment that never promised anything. If Alan were here today reading that article he still wouldn't be angry at the injustice of it all. It wasn't in his nature. He'd perhaps want to discuss it with his doctors but then he'd leave it at that. I on the other hand would be ready to call our doctors to reaffirm he was and had been in good hands, I'd have written letters and contacted the president of the hospital just to double check. "Soapbox Susie" is what Alan called me when I ranted about similarly infuriating exposees. Tonight he'd surely call me that. But after reading this article, one can't help but wonder about any radiation treatment that anyone has ever received and it certainly is worth asking about if ever faced again.

Deep breath. Sigh. Must go check on Lily, just to be sure of her.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Someone else's shoes.

An acquaintance of mine, with two children, just lost her husband to a long illness. When we first met there was so much that I recognized in her eyes - the concern, the exhaustion, the strength and the sadness. I remember seeing her one day, and she had told me her husband was in the hospital, again, and with resignation she shook her head and said "It's always something." I knew that sentiment all too well - feeling as though we were caught in the constant swell of a wave - nudged toward the shore but just as we could feel the sand beneath our feet we were dragged back out again, barely catching our breaths, treading water. Tragically, they too lost the battle. Though I have suffered similar circumstance, I am at a loss for words - and the frustration of not having anything of comfort to say saddens me to no end. But I know there is no way that I can console her. Her loss is profound and there is no "up" side.

What I want to say has much more to do with survival. I've suggested she just focus on getting herself to the next hour. To the next evening, then the next morning and so on and so on. I want to warn her that the world will look even more harsh, even more cruel. It will be even more painful to be in public, seeing the world go through its motions unaware of her loss. Sounds become a drone, people will seem out of touch and blatantly insensitive. Days will pass like dreams, waking moments will be nightmares. Most likely she will resent having to work, because nothing seems important when a life has slipped through your fingers, escaped hold of your heart. Almost everything will seem meaningless.

I am happy for her that she has two children for whom she must live. For no other reason she must hold on. And I would tell her to let those two blessings be her guiding light. I would warn her to leave herself alone. To let herself weep when she needs to weep whether it's at the bank or in bed. To let herself indulge in whatever soothes the aches - be it lying in bed, avoiding people or ignoring the mail. I would tell her to cling to her children, love them even more fiercely, eat, try to sleep and do it all over the next day. I would say don't make lists unless it helps you, don't say "I should...", just let yourself be. Let your body be. Let your heart be. Let your mind drift. I would suggest she allow her engine to slow down. When you take care of someone with a severe illness you are in constant motion, you do and you do and you do. And it feels as though that's barely enough so you push and you push and you push. And when you lose that person your mind and body will need months to unwind, and you will unravel in a way that leaves you feeling unsure, unsteady and doubtful of your abilities. I would tell her she's beginning a new uphill battle.

I would also say that although the journey is torturous, it is worth it.

I hated telling myself "you are fortunate to be alive" - because in the early days you are numb to that blessing. In my case, I loved Alan almost more than myself. When someone so dear to you is gone, life seems unimaginable without them. Though I knew I owed it to Alan to embrace what I was so lucky (and I think it is sheer luck) to have, for some time it seemed like a sentence, not a gift. Deep down I am sure that this woman knows life is a gift but for now it probably just feels cruel. I continue to have moments every day where I grapple with the unfairness of it all.

Being sixteen months "out" at times doesn't feel any better than one month out. In fact at times it is worse. I am still plagued with flashbacks and I am tormented by the "what ifs". I replay moments over and over in my mind and they continue to choke me mid breath and fill my eyes with tears. But I recognize that I have a purpose so I try not to linger too long on thoughts as they drift in the dark, and I try to focus on what I have, what Alan gave me, what Lily gives me. I recognize that I am needed and that I am so very fortunate. That is what I'd urge this woman to focus on - she is the center of her children's universe, and they, hers. So if she can just grab hold of that love, no matter how painful, perhaps in a year she'll be closer to where I am now. I know my life is richer having known Alan and I hope, at some point, that this woman allows herself to dwell on the beautiful memories she has of her husband - she will need those to pull her through the days. And when she shares them with her children, they will be lifted up as well and together, they won't move on, but they will move forward, slowly, but surely.

What I want to say has much more to do with survival. I've suggested she just focus on getting herself to the next hour. To the next evening, then the next morning and so on and so on. I want to warn her that the world will look even more harsh, even more cruel. It will be even more painful to be in public, seeing the world go through its motions unaware of her loss. Sounds become a drone, people will seem out of touch and blatantly insensitive. Days will pass like dreams, waking moments will be nightmares. Most likely she will resent having to work, because nothing seems important when a life has slipped through your fingers, escaped hold of your heart. Almost everything will seem meaningless.

I am happy for her that she has two children for whom she must live. For no other reason she must hold on. And I would tell her to let those two blessings be her guiding light. I would warn her to leave herself alone. To let herself weep when she needs to weep whether it's at the bank or in bed. To let herself indulge in whatever soothes the aches - be it lying in bed, avoiding people or ignoring the mail. I would tell her to cling to her children, love them even more fiercely, eat, try to sleep and do it all over the next day. I would say don't make lists unless it helps you, don't say "I should...", just let yourself be. Let your body be. Let your heart be. Let your mind drift. I would suggest she allow her engine to slow down. When you take care of someone with a severe illness you are in constant motion, you do and you do and you do. And it feels as though that's barely enough so you push and you push and you push. And when you lose that person your mind and body will need months to unwind, and you will unravel in a way that leaves you feeling unsure, unsteady and doubtful of your abilities. I would tell her she's beginning a new uphill battle.

I would also say that although the journey is torturous, it is worth it.

I hated telling myself "you are fortunate to be alive" - because in the early days you are numb to that blessing. In my case, I loved Alan almost more than myself. When someone so dear to you is gone, life seems unimaginable without them. Though I knew I owed it to Alan to embrace what I was so lucky (and I think it is sheer luck) to have, for some time it seemed like a sentence, not a gift. Deep down I am sure that this woman knows life is a gift but for now it probably just feels cruel. I continue to have moments every day where I grapple with the unfairness of it all.

Being sixteen months "out" at times doesn't feel any better than one month out. In fact at times it is worse. I am still plagued with flashbacks and I am tormented by the "what ifs". I replay moments over and over in my mind and they continue to choke me mid breath and fill my eyes with tears. But I recognize that I have a purpose so I try not to linger too long on thoughts as they drift in the dark, and I try to focus on what I have, what Alan gave me, what Lily gives me. I recognize that I am needed and that I am so very fortunate. That is what I'd urge this woman to focus on - she is the center of her children's universe, and they, hers. So if she can just grab hold of that love, no matter how painful, perhaps in a year she'll be closer to where I am now. I know my life is richer having known Alan and I hope, at some point, that this woman allows herself to dwell on the beautiful memories she has of her husband - she will need those to pull her through the days. And when she shares them with her children, they will be lifted up as well and together, they won't move on, but they will move forward, slowly, but surely.

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

The Great Communicator

It appears, within the last two weeks, that my daughter has acquired opinions. Her manners, in fact, have become outspoken, she pushes bottles away when she is done with them in quite a dramatic fashion - sometimes throwing them down or violently windshield-wiping it away frenetically with her hands. She has developed strong dislike for bananas (unless pureed) and avocado, a long time favorite is now officially "out". When she is offered either one, she whips her head into profile to express her distaste, the mere idea that they were even considered part of her diet a shocker to her, and ignores them until they are removed. If they are not removed, Lily is adept at doing so herself - she is a professional dropper and enjoys looking me dead in the eye as her hands do the silent work as though they are detached from her body. She has begun pointing to things which I am expected to get in a timely fashion and she now loves to hide items behind pillows, or in her lap and then make them appear again for me. We can do the hiding game over and over again - and she gets a thrill out of showing me her magic. Since the hiding game has begun I have found all sorts of things in hard to reach places, hours and days later. Only last week I found a rice cracker and orange stacking circle behind the couch, and a plastic cap in bed. I am reminded of a visit to my brother's when his son was a similar age and I noticed a jar of mustard in the toilet. We must be entering the "mustard age".

It is a whole new world now that she is connecting the dots, it is as though we are conversing. She is at no loss for words, and though they may need translation she loves to talk. Most items are now called "dah" but what's interesting is that with every "dah" there is meaning behind it. I can see it in her eyes, the wheels are turning, my curious girl is absorbing everything and any day now I expect I'll hear a word. Though Lily has her pensive moments she is proving to be more garrulous than her dad, I used to jokingly refer to him as "the silent partner" as Alan's words were economically used. He had his chatty moments but he was much more the silent observer. My favorite phone messages were from Alan perched in airport bars, they were always animated and even more humorously, long-winded. Perhaps Lily is channeling those moments. Or maybe she's a talker, just like her mama.

It is a whole new world now that she is connecting the dots, it is as though we are conversing. She is at no loss for words, and though they may need translation she loves to talk. Most items are now called "dah" but what's interesting is that with every "dah" there is meaning behind it. I can see it in her eyes, the wheels are turning, my curious girl is absorbing everything and any day now I expect I'll hear a word. Though Lily has her pensive moments she is proving to be more garrulous than her dad, I used to jokingly refer to him as "the silent partner" as Alan's words were economically used. He had his chatty moments but he was much more the silent observer. My favorite phone messages were from Alan perched in airport bars, they were always animated and even more humorously, long-winded. Perhaps Lily is channeling those moments. Or maybe she's a talker, just like her mama.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)